This piece was commissioned as part of the 'Crossing Borders' series.

‘We take ourselves through borders of every kind and carry no passport.’

Deborah Levy ‘Beautiful Mutants’

1

I once wrote a piece of short fiction that began with the words ‘This is a true story’. It was not true in any sense, as in the story the characters’ actions are set in motion and orchestrated by a murmuration of birds. The story begins when a woman sitting on a train happens to see a heart shape in a flock of birds and takes this as a message sent exclusively to her. In a similar way to the film ‘Fargo’ in prefixing the narrative with the claim that this was a ‘true story’ I was playing with the notion of verisimilitude and the gravitas of truth.

To be precise, I began that story while I was sitting on a train and had been staring out of the window when moments before, I saw, for the briefest moment, a heart shape evolve then dissipate in a flock of birds. So that part was true but everything else in the narrative was a lie. Or rather it was that loftier term used to describe artful lies, fiction.

2

One word that has never been used to describe my writing is ‘authentic’. I noticed this once, very acutely when I read one of those shared double reviews where two similar books are covered together; my book was described in various ways, but the other book, which was also fiction, was described as ‘authentic’. This seemed curious to me, perhaps because the implication was that my work was ‘inauthentic’ and that seemed a criticism of sorts. In my writing practice I had always created fiction out of the pure ether of the imagination, or had so altered the characters and circumstances of lived experience so as to no longer bear any resemblance to the real situation or myself, my friends, lovers, family or other acquaintances. I had always wanted my work to be authentic in the sense of being real in its own terms, but I worried, was I missing something?

This battle between the real and the imagined seems to lie at the very heart of fiction. Should novels and short stories be created out of invented characters and situations or should it be disguised autobiography? For me it was always the former and yet a story about revenge I wrote a very long time ago was mentioned in a court case to prove my dangerous devious and vengeful nature (I should add here that I was not accused of any wrongdoing and it was not a criminal case.) That the moral of the fiction I had written argued very clearly against revenge; explaining that it can ultimately only hurt the person attempting it was entirely overlooked. The story was described in a statement as proof of my awfulness but not offered up in evidence either complete or in part. Real or unreal, my capacity to even imagine a scenario of revenge was apparently proof enough of my untrustworthiness. I was so distressed by this entire situation; seeing my life, my hard won and beautiful creation used against me, distorted and misunderstood, that I almost wondered if it was true, that I might be this evil character I was painted as. Therein lies the borderline between madness and sanity; the liminal place where the solid ground you stand on falls away and you are left suspended in space, uncertain of not only the particular events that led you to that moment, but everything else too.

3

It seems that if there is a border between sane and altered states of being and thinking, it is a soft one, shifting through gradual shades of grey, vague, mutable and shape-shifting. In our dealings with others we may not be fully aware of their state of mind and if they are transitioning from a relatively ‘normal’ state to another this may be unavoidable; for how can one judge? Perhaps it is only with hindsight that the truth of any interchange emerges.

Many years ago I was at college with a woman; I’ll call her X, who to all intents and purposes, seemed quite ‘normal’. Like me she was a mature student and a single parent. As we each had children who were close in age I invited X and her daughter to Sunday lunch. The plan was that following the meal the two girls could play together while we chatted. Once we had eaten the girls were eager to escape and went into the next room, where as well as toys of different kinds there were art materials. X had brought along two used bridesmaids’ dresses for the girls to play in and they put these on immediately. Then the inevitable happened and the clash of our two very different styles of parenting emerged when X noticed that there were a few small splashes of watercolour paint on both of the dresses.

In terms of our different approaches to parenting I saw play as a zone of creativity where things, clothes in particular might get dirty. X thought very differently. In my view the dresses (the wedding they had been bought for being in the past) were for playing in and if it had been essential that they be kept pristine they should not have been brought. However, not wishing to fall out over the matter I assured her that the paint would wash out very easily. There were but a very few pale splashes anyway and they were hardly noticeable.

A few days later X came up to me in the college café and handed me a large plastic carrier bag. ‘Here!’ she said. For a moment I thought that what she was giving me was a gift; a marker along the way in a blossoming friendship. The bag was very heavy, ominously so. I looked inside and saw folds of white satin. Wet satin, I might add.

‘You said the stains would wash out. Well, they won’t. You wash them!’

So saying she stalked off, leaving me, as in some twisted fairytale, encumbered not only with the hefty pile of college books I was already carrying, but the two stained and sinful dresses. I took the dresses home and washed them, but the stains, although they faded to almost nothing, did not entirely disappear. Having failed at my accursed task, I dried the dresses, put them back in the bag and left them in the hall meaning to return them to her. Yet I hesitated. How could I return them with the stains still visible? I did not even want to talk to the woman. I had made an attempt at friendship, invited her into my home, fed her and her daughter, and she had returned my gesture with this unpleasantness. Yet if blame for the ruin of the dresses could be apportioned, then it fell on X as much as on me.

4

I had troubles aplenty at this time in my life, having moved back to my home town after more than ten years in London. The friends that I had once had had left or moved on in their lives, while my friends in London were too distant and I was too poor to travel back and forth to see them. College seemed the place where new friendships might be formed and yet a number of factors made this almost impossible; notably the demands of being a parent, the age difference between me and the majority of students, and lastly money - or rather lack of money.

X had unsettled me, in some ways she frightened me, perhaps even reactivating in me certain fears that stemmed from years of being bullied and physically attacked at a tough comprehensive school.

5

I never took the dresses back into college and X never asked for them. They stayed in their carrier bag in the hall; hateful things that I could not allow my daughter to dress up in, nor could I bring myself to return them or throw or give them away. After a time, sick of the sight of them, I put them in the cupboard under the stairs.

Time passed and X disappeared from college between one term and another. The rumour went round that she was at the local psychiatric hospital following a breakdown. Then we heard that she had been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Her story ended disastrously, but I mention it only to reveal how the perception that everyone we encounter in our lives is acting rationally and therefore perceive the world in the same way we do is not always the case.

When she’d pressed the carrier bag containing the wet dresses into my hands I took her actions to be spiteful and arrogant and downright mean. I did not see it as a symptom of a state of mind that was damaged or distorted.

How she saw me I do not know, but later it emerged that one aspect of her particular set of delusions was that she believed that the kindly man who lived in the flat below hers was sending mind control signals up through his ceiling and her floorboards to infect and influence both her and her daughter. Knowing this I cannot help but wonder if, following that disastrous lunch, she and I stood on opposing sides of a distorted mirror. So that, while my actions and responses were, to my mind, natural and well-intentioned and reasonable, in her mind I represented someone who wished her harm. Perhaps she thought I had infused the bridesmaids’ dresses with an indelible poison; that like the hair and fingernail parings a witch might use, were there to do secret damage. Perhaps that is why she never asked for the dresses back and may explain why she gave them to me sopping wet, so urgent was her need to be rid of them.

X must have alienated so many people with her seemingly mean behaviour, driving a wedge between her small family unit of two and the rest of the world. Her daughter died in very troubling and mysterious circumstances within a couple of years of the incident with the dresses and X died by her own hand, a few years after that.

6

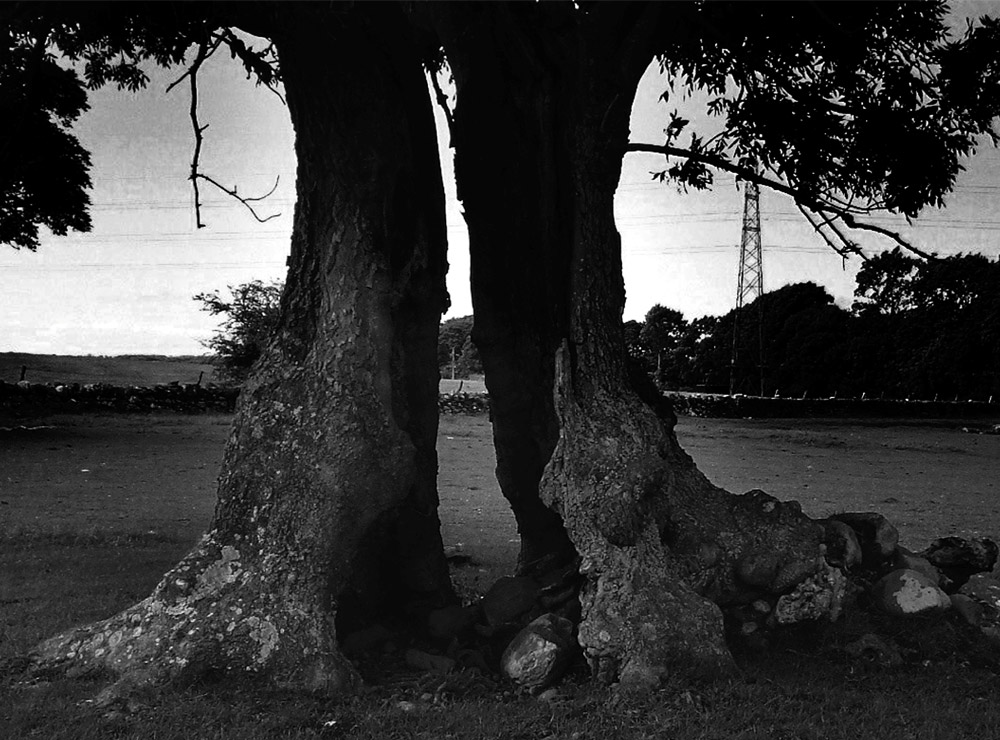

Most of us fear the loss of our minds to the diseases which come with old age. Jonathan Swift, seeing a tree that was dying back said, ‘I shall be like that tree; I shall die at the top’ thereby predicting the senility that would soon afflict him. But there is also the danger all through life particularly in times of stress and trauma when reality seems in danger of slipping away. The incidence of depression and other forms of mental illness are high amongst writers. Perhaps it is the nature of the work which causes this as it is typically done in isolation both in the practical and emotional sense of the word. Or perhaps it is that personalities with particular tendencies; sensitivity, imagination, curiosity and a melancholy temperament are drawn to writing.

Angela Carter in her story about Lizzie Borden in ‘The Fall River Axe Murders’ draws an intense and vivid portrait of a woman so constrained by circumstance; by biology, by a corset and layers of petticoat and other conventions of female dress unsuited to the August heat in Massachusetts that she went mad and killed her father and step-mother.

7

Writing a novel means that for a sustained period of time its author dwells in an invented world; this is not dissimilar to the daydreams and fantasies all humans experience. I would argue that when writing one goes into that world very deeply so that like a diver coming back up care needs to be taken.

8

Like Lizzie Borden, in 1796 Mary Lamb, who together with her brother Charles later wrote ‘Tales from Shakespeare’, suffering under the stresses of her pinched life had a breakdown and stabbed her mother to death. Both Lamb and Carter’s version of Borden seemed to have exploded into a state of murderous being from inside the shells of restrained and straightened domestic life. The corset Borden wore, a prison squeezing her flesh and internal organs day after day a special kind of torture. I say ‘Carter’s Borden’ because it remains uncertain if she had been the culprit. Borden was not convicted of the crime despite the skipping rope rhyme:

Lizzie Borden took an axe

And gave her mother forty whacks.

When she saw what she had done,

She gave her father forty-one.

9

How does a writer dealing intimately with a variety of states of mind and the challenges facing her or his characters both enter into their consciousness empathetically and also protect themselves when they put down their pen or close the lid of their laptop when they must return to ‘real life’? My guess is that the border between states of mind is soft and malleable; we drift from the real and the imagined on a constant basis; sometimes thinking back to what we decided an hour ago or remembering an event from long ago, then a second later we are forward planning to the end of the day or to a month or year hence, while at the same time existing only in this moment and this moment and this moment.

Depending on their technique a novelist may know exactly what is going to happen in their narrative; they plot then, as it were, dress the skeleton of their story. Others, and I am among this latter group, begin writing with a vague notion, then seemingly discover the story as it develops. Neither way is right or wrong, but the second perhaps more resembles real life in that while a person might set goals and hope for certain outcomes, unexpected problems arise to change things.

Is there a link between my way of writing and the sort of psychological outlook or mind I have? That others have? Perhaps because I was self taught as a writer I have stumbled upon this as a way of working instead of choosing it. What I grow are mushrooms; I seed them, then mysteriously they appear. Or sometimes don’t appear. At certain times I think that a well-tended orchard would be so much easier – straight rows of trees, well fertilised, spring blossom, then autumn fruit. A plan set out, maintained, fulfilled.

10

The poet Ruth Fainlight has written very vividly of her sense of guilt about her failure, despite many attempts, to save her mentally ill brother, Harry from self destruction. In a similar way I regret that I misread X’s state of mind and actions; the distance of my relationship to her ameliorates this somewhat, but not to the point where I feel no guilt at all. I could not help her and furthermore she affected my own sense of well-being – so the destruction was more widespread than one might think.

Reading about the lives of those afflicted with mental suffering whether delusions or depressions can inspire the reader to wish to almost reach back in time and shake them from their torpor or folly. The account of the writer, Rosemary Tonks’ destruction by fire and hammer of her collection of Oriental and Persian treasures in 1981 is heartrending both for the loss of the objects themselves: Tang horses, Chinese jade and bronze and embroidered silk, but also for the mind which had become so distorted. Into this same fire went the manuscript of the only novel she had ever written.

11

The last time I saw X happened when I was sitting on a bus which had stopped to pick up passengers. I noticed X on the other side of the road staring intently at the waiting bus and evidently wanting to catch it. With her was a mangy-looking mongrel with a piece of rough hairy string for a lead. X dashed across the road when there was a gap in the traffic but hadn’t noticed that the bus driver was about to move off. She ran right in front of the bus causing the driver to slam on the brakes just in time. He opened the doors to let her onto the bus and as she mounted the steps he said, very angrily, ‘Are you trying to get yourself killed?’

His words represented that common assumption we have about other people; we think they are just like us, that for them self-preservation is paramount and we do want to get ourselves killed. By that point in her life I don’t think she cared. Our world is increasingly hard enough, cruel enough, uncaring enough for even those with the soundest of minds to despair at times, but for those who have journeyed over that fragile border into mental illness, the fight for survival is perhaps more easily abandoned.

Image courtesy of Jo Mazelis

Jo Mazelis

Art school dropout, writer, photographer and lover of Welsh mountains

SEE PROFILE