I travelled to Athens for the first time a few weeks ago. I had never been to Greece, yet always had a strong emotional relationship with that country’s culture, people and history. I was born in its neighbouring Turkey and, although my parents emigrated to Belgium when I was a baby, Turkey’s culture and history – through language, literature, my family, friends and heritage – have always been part of my identities. Flying back from Athens to Amsterdam, where I have been living for the past decade, I shared this short post simultaneously on Instagram and Facebook. I have expressly written it in Turkish, choosing my words with immense care, trying to convey the emotions I felt in Athens as a woman with Turkish heritage – not as a francophone Belgian citizen, not as an Amsterdammer mixing Dutch and English throughout the day. Using the Turkish language while writing the post was key: I wanted Turkish speakers, especially my friends and family, to read it, and all non-Turkish speakers to see that the post attached to that specific image – and feeling – has been written in Turkish.

While Instagram offers the option to translate the post, Facebook automatically showed a translated version of my thoughts in people’s feeds. (I later realised that automated translation can be switched off in the settings, giving viewers the option to have the post translated into their preferred language by clicking “Translate”.) That conscious act of clicking versus the automatic reception of a post written in another language as if it were written in your own, can influence the reader’s interpretation of the message. Moreover, it irks me that Facebook can have that kind of power over my voice: which language I use is always a deliberate choice on my part. The fact that I am a control freak probably plays a part in my level of annoyance, but there is more. Inherently, it has to do with what translation means to me, as a professional literary translator and writer, and the fact that I approach most of my languages emotionally.

Picture illustrating the Facebook/Instagram post mentioned above.

I have a very specific view on what to translate and how translation should be performed. To me, translation is resistance, and so it requires action. Automated translation, on the other hand, does not require the writer or the reader to take any conscious action. While it certainly is practical in many cases, it raises issues when we are dealing with creative content. The way I write in French is not similar to the way I write in English. The context matters, in the case of my initial social media post from Athens, it is about the connexion between Turkey and Greece and the strong emotions this trip triggered in me. Even if the reader will click on the translation button to understand what I am conveying, she will know “where” it comes from. If she sees the content immediately in the language of her choice, she will miss that sensitivity and read a poor translation of what I have initially tried to say. This simple social media post may not count as literature, but those platforms are places where I express myself as a writer and a literary translator, and those words too require creativity and imagination. Automated translation is not yet ready to render that as I would wish it to.

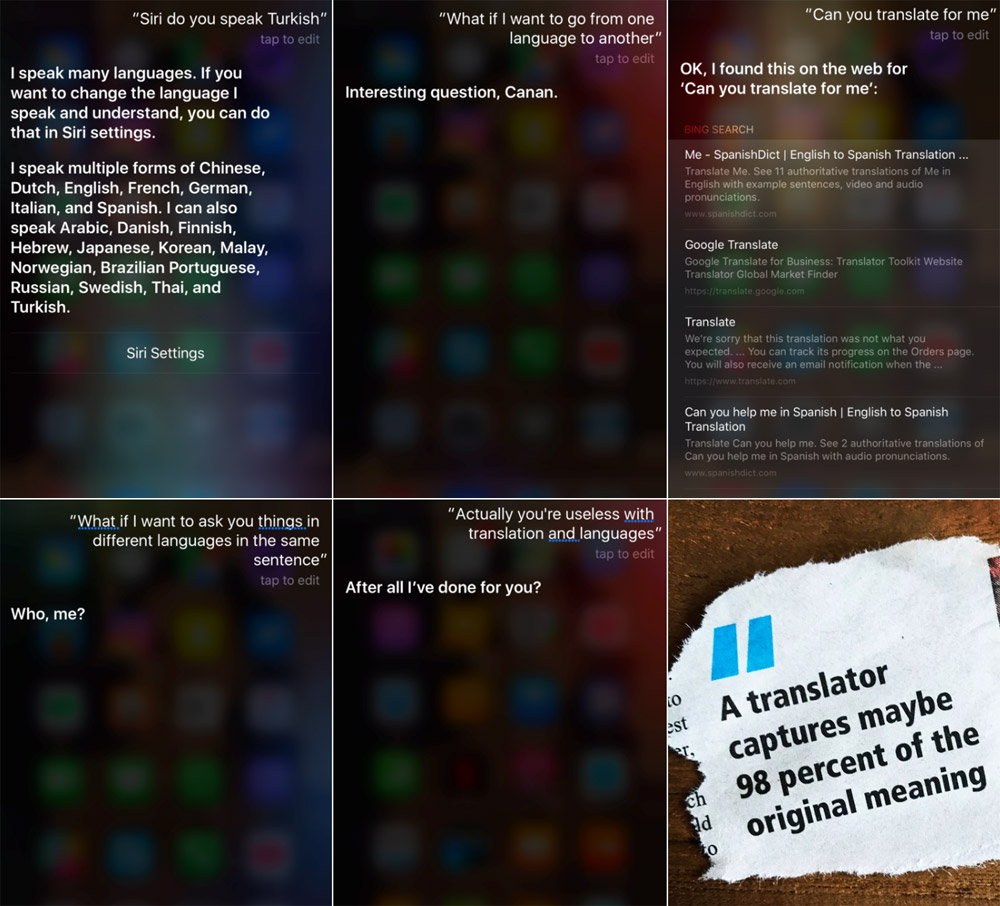

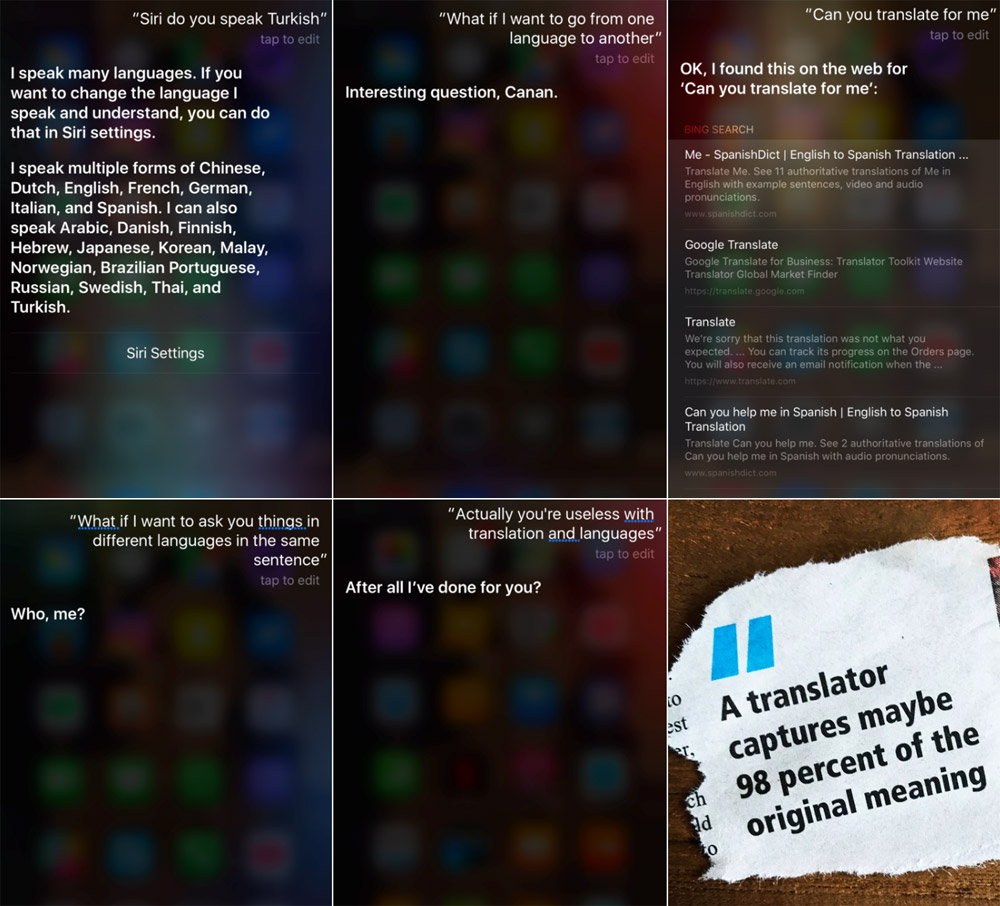

Facebook’s automated translation raises important questions for me: in what ways is technology shifting our notions of translation? What does that mean for us today, and what might it mean for literary translation in the future? From the perspective of an algorithm, is there any intrinsic difference between translating a novel and translating a business document? I yearn to say yes, but I do not know, and that is a problem. I am no luddite. While I do feel wary about having a statistical machine translation rendering my voice, I do embrace the advantages such a tool brings to users, and I am certainly one of its many beneficiaries. I know how Google Translate works (yes, I Googled it). I use Google Translate when I translate literature. I also check several online (and more and more rarely offline) dictionaries when I come across a word or an expression I do not know. When I translate, Google is always my friend, because I do so in different languages and it is able to switch between them (that’s why Siri remains useless to me; it can’t work with more than one language at a time). I look at many variants before I can select what I feel is the right translation. Literary translators know the so-called right translation can be subjective and depends on our own interpretation of the source text, and our knowledge of the languages and cultures we work with. Ultimately, having access to a lot of data is a good thing for literary translators, as long as we know how to use it. We do literary translation, not literal translation, we don’t just copy/paste content no matter if it comes from Google Translate or the Oxford Dictionary. When used wisely, technology can offer many advantages, help us develop our craft and gain a lot of time. But we cannot leave it to the A.I. designers to solve issues of literary translation. Our knowledge and expertise of creative writing and multilingualism as translators shapes the way we look at the world tremendously. We can explore many sensitivities across different geographies and build bridges between a variety of discourses and stories. While some A.I. designers may share some of these skills, this is probably not what they prioritise. And many of us are not trained to think in terms of algorithms and their impact on the way people behave. We therefore need to join our efforts if we wish to build better tools. Google, Facebook and many A.I. designers do not seem to be looking at literary translation – at least not yet. Why is it so and will it always be like that? I don’t believe they will ignore us long, and once they turn their attention to us, we should be ready.

Collage of Canan's attempts to talk with Siri, ending with a newspaper quote published in an article about literary translation in Copenhagen (2015).

Machine translation is not new, in the early fifties, the Georgetown experiment involved successful fully automatic translation of more than sixty Russian sentences into English. Such attempts may seem purely mechanical and fall short when dealing with literary translation. Our craft –like other expressive endeavours, is defined by creativity, by the knowledge of cultural, sociological and historical contexts, and as Rob Girling writes about design, it is also about problem framing, creative problem solving, about negotiation and persuasion. To achieve the impact of the source text, literary translation also requires us to tap into our emotions and have empathy. And machines cannot have empathy, right? Girling starts his piece by pointing us to a new research centre at Carnegie Mellon University that will explore ethics of A.I., arguing we can no longer doubt its presence and impact on designers’ work. I believe it is valid for our field too. Many examples in science fiction invite us to reflect on the nature of consciousness and see robots as sentient beings, and the fact that Carnegie Mellon University will create a research centre that focuses on the ethics of artificial intelligence confirms the need for such reflection. Works of fiction have shown us different ways translation could work: Doctor Who’s TARDIS has a universal translation system based on telepathy, and in Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, we have the Babel fish. I love how these work, but they tend to function more like Facebook’s automated translation option. I have more recently been fascinated by how translation has been portrayed in the film Arrival, based on the novella Story of Your Life by Ted Chiang, starring Amy Adams who plays linguist Louise Banks and is asked to decipher the language of the heptapods – the aliens that have arrived on Earth. Google Translate would of course be useless here, since there is no existing data entered in the system about the heptapods’ language. But this story is not about data, it is about building a bond and about empathy. Although the pace at which Banks manages to decipher patterns and starts communicating with the heptapods is thanks to the available technology, the film goes far beyond that and shows us how language shapes reality. The aliens’ language is tied to their perception of time as non-linear and Banks’s perception of past and future shifts accordingly as she masters the alien language. I am not saying that translators are psychic, but they perceive the world differently. As polyglots, we can receive and create multilingual data. And our ability to move between languages allows us to embrace, and act on, empathy. Being able to access and understand literature, the news and other resources in five languages offers a variety of opinions and ways of looking at the world. I consider myself privileged to be able to do so, but I am also imagining a world where accessing and using such knowledge could become as effortless as going on Facebook. I am bemused by this consideration: one the one hand, it scares me to become irrelevant, while on the other, this conversation excites me tremendously. I am curious about what the future will bring and how it will impact our societies in general. Moreover, I want to engage with these developments.

I do believe that one day, machine translation will be so advanced it will be able to translate literary works of fiction and non-fiction, and, working with other algorithms such as Amazon already does, it will also be able to select which types of works from which authors and which languages could be marketable. This does not scare me in itself – the more translated works are available, the better. Also, a lot of publishing houses do curate their offer based on what is marketable. But we will always need to also work outside of the market’s needs if we want to offer wider diversity of voices from different places – and this is my focus as a literary translator. That’s why I do not believe any A.I. will be able to do what I do, any time soon, but seeing the current advances in the field, I may be in denial. Maybe I am afraid to ask: is there something inherently different about literary translation, and are literary translators an endangered species? The truth is, I don’t know. After all, with the right algorithm, and if A.I. will one day have sentient capabilities, why couldn’t it – or should I say she – do what I do? Instead of doubting, maybe I should try to work with her. Extending the horizon of possibilities allows us to ask questions that may sound implausible today, but even as a thought exercise, it allows us to investigate the nature of our work. What does the world of book publishing look like when readers can evaluate books without having to care what language they were originally written in? How do trends and tastes evolve when all books exist in all languages simultaneously? Will we have favourite algorithms for translating books, like we have preferred translators?

But that future still seems not so close. I am still mad at Facebook’s artificial so-called intelligence ineptly sucking the life out of my original post by erasing the key connexion between my language of choice and the place I wrote about. And yet, as publishers, writers and translators, we need to have a collective reflection on how A.I. will impact literary translation in the future. We first need to acknowledge that technology develops at an extremely fast pace and that, no matter how much we may object its effects, it will continue to evolve with or without us. Then it’s up to us to create spaces where we can openly discuss our hopes and fears about the changes A.I. may bring to our field, and when we’re ready, we should include A.I. designers into our conversation – or join theirs.

While our role and workflows might need to evolve, as ever, with the times, in the absence of true A.I., there will always be a place for judgment, a need for empathy, and therefore human literary translators. Predicting the future is especially tricky when it involves humans and culture in any way, but if one thing is certain, we can’t afford to ignore the changing world around us. As a literary translator and a writer, I don’t want to passively watch and wait, I want to be part of the conversation to help bring literary translation beyond automation.

About Canan

Canan Marasligil is a freelance writer, literary translator, editor and curator based in Amsterdam. She works internationally in English, French, Turkish, Dutch and Spanish. She specialises in contemporary Turkish literature as well as in comics. Her interest is in challenging official narratives and advocating freedom of expression through a wide range of creative projects and activities. Canan has worked with cultural organisations across wider Europe and has participated in a range of residencies at the Free Word Centre in London (2013), at WAAW in Senegal (2015), at Copenhagen University (2015) and at La Contre Allée in Lille (2017). She is the creator of “City in Translation”, a project exploring languages and translation in urban spaces.

Find out more at www.cananmarasligil.net and www.cityintranslation.com