Commissioned as part of the ILS' 'Crossing Borders' series.

The difference begins around midnight when stark light invades his window and the thunder of machinery erupts. Geoff rises and walks across the room. He stands to one side, shielded by musty curtains. There’s a routine clang of metal on metal that’s shrill as a high-pitched voice, an equally repetitive thud of helicopter blades. He hears shouts, the raw scrape of tools. Something pounds the earth, making his sash window frame rattle and when light brightens the room in a monochrome glow Geoff steps away, pressing his back against the cool wall. He pushes one hand against his lips so hard it begins to hurt. He realises what he’s doing and returns to his desk.

For some time he doesn’t know what to do. He plays with the black mouse on its mat. He gnaws loose skin beneath his thumbnail. He throws back his head, and sighs deep, swearing between clenched teeth. In a fit of anger, he swipes at his phone. One knee bounces. Unlocked, he touches favourites and calls home.

‘Mum?’ Waiting, scowling. ‘Hello? Yeah, it’s me. I know you know, I’m just saying. You alright? Yes, it’s late. No, nothing’s wrong it’s just… Look, they’ve started… Yes. I don’t know. Right.’

She doesn’t have much to say beyond the platitudes most parents grow used to, especially those who’ve long drifted from the practice of daily calls with their child. He tries not to get too upset with his mum and dad for their lapses, yet if he’s honest the passage of time is beginning to scare him. That relentless creep towards an unseen future of before it happens and who knows after. The realisation he’s seeing some measure of his own fate. He’s noticed little changes in their manner, a lack of reasoning, the forgetfulness, an inability to move as well as they once did and their shortened tempers, all transmitted by phone or Skype these days, but even when he visits he sees so much. Markers of time. They’d crossed a line back when Geoff lacked full awareness, tipped over an unseen edge into slow decline. He’d seen it coming too late, worried for scant seconds before replacing the weight, the greying hair and sporadic amnesia with more immediate problems, mainly his own. And now there was this.

‘Don’t worry about it, yeah? I’ll get it sorted. I know they said but there’s got to be a way. I’ll see about it in the morning and let you know when I do. I know. Well, at least you and dad are OK. That’s the main thing.’

He blanks out when she talks of all the things he’s used to, only to realise and snap out of it. What’s he doing? What was he just telling himself? He nods, shuffles his mouse, picks at his jeans.

‘’Bye mum,’ he says when she trails off. ‘I’ll call soon OK? Love you.’

He doesn’t wait for her reply and cuts off the phone. Thunder brightens the room. This time, he won’t look.

They’re out there for the rest of the night. Radios playing bland pop, pounding tools that echo across the bare expanse of moist, sodden earth. The fairy tale tinkle of fallen nails and grunts of heavy goods vehicles over a random whirr of drills. The searing noise of a cutting machine makes Geoff start, half rising. He’d dreamt of a circular saw, a fountain of sparks, some tough material or another shorn away, bending like paper. He sits up, drinks his bedside water and stares at drawn curtains. He can ignore the bastards but they won’t go away.

Morning brings relative quiet. Geoff eats granola to a background noise of occasional hammer blows and various mechanical devices, although he also hears birds and the roar of planes. He spoons cereal, chewing thoughtless mouthfuls, pushes the bowl away and stands. He grabs his keys, his ID and leaves the flat. The door slams behind him, shuddering in its frame.

The stairs are dark, the grey walls cold. Faded graffiti is smeared in bleached unreadable patches all the way down. He pushes the icy steel bar out of his block and into the bright of day. Altostratus clouds veil the sky. The sun’s mute as if hidden behind ground glass. Geoff pushes his hands into the pockets of his denim jacket, hurrying along the black gravel path, slipping on the odd mud patch. It’s cold and he’s hunched against a growing breeze. The pop music’s louder, irritating. He turns the corner.

Egg-speckled columns somewhat like motorway struts are placed in a single file line, maybe spaced four hundred metres apart, it’s difficult to tell. He’s stunned to a halt. They stand high, towering over the building that contains his one room flat by at least another half block, perhaps. Geoff understands last night’s need for loud machinery even as he marvels at how it was done. They hike across the shattered remains of the worn town, far into the greying distance. Between each T shaped strut there’s an odd, shimmering trick of the light that reminds him of childhood, the translucent film of bubbles he blew as a boy.

For years they’d threatened to build a wall and eject those who sought to destroy their way of life, to safeguard and protect freedom as if it were a stolen foreign jewel, seen but never touched. They’d made plans and held referendums, argued for and against although in truth there was never any question. While London burned and terrorists murdered innocents, people grew ever more fearful. The iron will they were proud of grew brittle with rust, only a matter of time before it snapped, fell away. Exposed to the elements, corrupted from outside by political businessmen who barely lived in the city. And so that final vote, to expel not only foreigners but also the less wealthy, had been enough to make it keel and die. Those who voted against were right when they said the results might possibly last forever.

He turns away. Not far from where he walks a lumbering group of pre-adolescents test the wall by throwing stones. The transparent material sparks and glimmers with each contact, a hissing snake. Stones chip into pieces and fall to the mud as if striking concrete. Geoff wants to give the youths a dirty look, but instead he does his best to ignore them. Idle workmen see what’s happening and chase them away.

He over emphasises his strides so he can make headway over loose soil. Gravel scrunching, escaping underfoot, he keeps his hands in his pockets, trying not to fall. He passes workmen in hardhats, their frames squat and shoulders broad, suited men gathered around ATM-sized computer banks analysing dark screens of information, and the inert figures of lifeless machines; diggers, flatbed trucks, others he’s never seen. Beyond them, a larger group of people mill, forming a knot of crowd. There’s no shimmering film, just open space. Geoff gets close before he sees it’s actually two separate groups, easily discernible at that distance. The nearest stand with their backs straight, dressed alike. Coming behind them as he does, without his glasses, he has to squint before he sees they’re the army. The further group are dishevelled and broken. Geoff notes mucky faces, the single file queue. Many are covered in blankets, hunched. Some limp away from the soldiers to gather beside a white bendy bus at the bottom of a grassy incline. Civilians, he tells himself. Rejects.

He circles the soldiers, pushing to the front of the queue. The waiting people shuffle and give him bad looks, but even now they do that typical English thing and remain silent. Three soldiers dressed in fatigues, two men and one woman, stand by a makeshift desk and computer set up scanning ID’s and fingerprints against names on the screens, checking them off, sending the relevant person on their way. Geoff begins to smile, forcing it from his face. Be calm, he warns. Another four soldiers are poised in varied positions of battle readiness, hands on rifles, scanning the crowd. As Geoff moves closer, the largest steps towards him.

‘Can I help?’

He feigns another smile at the giant of a man, all lips, no teeth. The giant looks through him. He imagines the man’s thinking of the best place to put a bullet if he makes a sudden move. He’s blonde, wide faced, cheeks flecked red.

‘I’m alright actually. Just wanted a word with Lieutenant Parks.’

She looks up from the screen, eyes wide before she composes herself.

‘Mr Morgan. Are you OK?’

‘Yes, I am.’ He’s less sure, thrown by their need to negotiate the moment as strangers rather than what they are. If anything. ‘Is it alright to speak for a minute? Won’t take long.’

Parks turns to the giant. She blinks, lips pursed and he steps back into position. Her colleagues try to keep their attention on the civilians. She walks away and Geoff follows, trotting down the incline until no one’s close, between the bus, the people, the shadow of his block and the closest strut.

‘What’re you doing?’ she’s hissing. ‘You trying to get us both in trouble?’

‘No, I just… I didn’t know you’d be here. How would I?’

She softens, more like the woman he knew by lamplight in the empty confines of his local. Her deep eyes are still gaunt and hard, exposed by the tightness of her wrenched back hair, but her shoulders fall. The tiny mole to the left of her lips makes her mouth look like it’s pouting when she’s really not. She snatches a glance behind her.

‘So what do want?’ she says, less accusing, even though her hands are on her hips. She peers at Geoff like he’s the foreigner.

‘I need to get home. To my parents. They-’

He can’t say it. Instead, he toes crumbling earth. Parks sighs, breath whistling in time with the low wind. Silence stretches.

‘Look. We’re getting concessionary passes,’ she manages. ‘For when we’re done. Two a man. I’m don’t need them, so…’

She looks at the civilians. She’d told him that night, of lights out at eight, the shared bedroom and unfeeling care home staff. The waiting for adoptive parents that never arrived. Geoff floods with elation. He barely stops himself from hugging her.

‘Thank you. That’s-’

‘Go home. Stay there. I’ll come round at twenty-three hundred hours.’

She pivots, going back to the desk. Geoff tries not to stare at her rear, the twin curves easily visible beneath loose fatigues. He moves away.

A woman he’s never seen before is leaning face forwards against his block wall, arms covering her head, body trembling and bent. A limp hoodie falls halfway down her back. He sees the peach strap of her vest, the black bra strap beneath. Her skin’s pale, her deltoids ridged, although small. She’s a sorrowful void against rough walls.

He can’t very well ignore her, not after Park’s kindness. Geoff slips down the incline onto the path, standing beside her for a series of useless moments.

‘Hello?’ he says after time, one hand raised above her shoulder.

She ignores him. Behind her, former Londoners trail onto the white bus, heads turned to watch. Geoff eyes the soldiers. They’re busy filing people through the open gate.

‘You’ll miss the bus. You need to get to the displacement centre or you won’t be rehoused.’

The woman sobs louder. She’s tall and skinny, her hair cut masculine short. She wears tight jeans and that thin hoodie. She must be cold.

‘Look, do want a cup of tea? I might be able to help. I know a way to get back into the city.’

She doesn’t react for some time and he’s about to give up until she lifts her head. Her eyes are tower block grey, saturated by red. Her nose runs in delicate strings. She doesn’t seem to care. She hiccups, stares.

‘Come. Let me get you inside, I’ll explain.’

Geoff sweeps an open arm towards the path. When he leads, the woman follows.

She perches on the edge of his sagging three-seater, a mug in both hands, focused somewhere behind him. Geoff sits at his desk opposite, misted by his own steaming mug of tea. She only speaks when he asks how she’d come to be ejected from the city, her voice tinged with a Spanish accent. A CEO husband heading one of the big five housing associations, a six-bedroomed relative palace in Golder’s Green. A near-perfect son about to begin secondary education at a leading private school. She could have remained a housewife and claimed her husband’s income on the census, but she’d started her own cleaning business, as that’s what she did when they met, and she was proud not to rely on him. Little did she know when the vote was taken there’d be two strikes against, one for her country of origin, another for her lack of personal wealth. She’d been blacklisted without anyone’s knowledge until the declaration of section one eight two. The night before last, the order was implemented.

They’re silent when she’s finished. Now she’s told him who she really is, the difference between them is startling. Her thin, sitting upright and taut with the muscle that comes from hard work, him podgy, slumped in his office chair. Her thick with an accent that makes her speaking voice difficult to decipher, him articulate, well thought out and clear. He finds it tough to imagine her wandering a six-room mansion, or dropping the son off at school, hurrying him through tall gates. She doesn’t look the type, more like an immigrant fallen on hard times wearing a drug dealer’s jacket. It seems odd that even with all Geoff’s upbringing and education he should end up here, in this flat, and she there. The difference produces an acid burn in his stomach he can’t entirely put down to not having eaten since breakfast, or the tea.

‘What do you do?’ she says, indicating the laptop.

‘I’m a journalist actually. For the local rag. Only I haven’t written for them in a while.’

The truth was they’d let him go. Budget cuts, they said. He’d been living on meagre funds borrowed from his parents for the last nine months. Stubborn, not wanting to leave. And now this.

But of course he can’t say that. Scraps of truth lodge between his teeth like meat. He clenches his jaw.

‘I have an army friend down there; you might’ve seen her,’ he tells the woman. ‘She can get passes.’

The woman shifts, uncomfortable. Her face is drawn with lines beneath the bare light.

‘And you’d give me one?’

‘Of course.’ He stretches his lips in another toothless smile.

Her eyes are opaque. She’s trying to keep them open, obviously struggling.

‘Thank you. Thank you…’

‘No trouble at all,’ he sing-songs. ‘You can pull out the sofa bed if you want. I’ll take the laptop in the other room. I won’t disturb you.’

The woman looks confused until he gets up, removing his laptop from its stand. She takes off her shoes, swivelling horizontally. She’s lying down and doesn’t have on socks.

‘What’s your name?’ he asks from his bedroom door.

‘Nuria.’

‘I’m Geoff,’ he says, and pushes the door closed.

He writes an article for a friend’s blog, something inane about the falling teenage pregnancy rate in his locality. He makes a good attempt at getting back into it until the outside begins to call, distracting him from the white screen. He grunts and shuts the laptop, banishing words. He walks over to his bedroom window. Voices float on thermals. Civilians stream from the makeshift checkpoint. Three bendy buses stand in line, doors open, engines purring like cats. The soldiers corral their charges towards the vehicles and he can’t see Parks but knows she’s there, performing the job he can’t quite believe is hers. The magnetic wall shimmers purple and blue under sodium lights like trapped nebula beneath glass, a series of installations that extend forever north.

Geoff checks on Nuria. She’s sleeping, comatose. He makes a bowl of cereal and sits at the desk, watching. That good feeling, the one that came with the elation at finding a way into the city and giving aid to a fellow human being, gives way to something else. He can’t quite recognise what, but a thought rises. His lone voice. Who’s the victim, it asks. Geoff’s spoon is poised. He waits for an answer. Me and you of course. Me and you.

He shakes his head, attempts a laugh. All he expels is a soft rasp, more like a wheeze. He shuffles in the office chair, eats another spoonful. Me and you, he thinks, me and you.

Even so, he can’t quite picture the balance. Although he’s well aware it’s not entirely accurate, Geoff eats cereal, imagining a pair of antique scales that tip against him every time.

The knock comes just before eleven. He pads out to answer as Nuria’s still curled up, snoring like a child. When Parks follows and sees the woman on his sofa all colour leaves her face. She gestures, harsh whispering. He puts a finger to his lips, beckoning her into the bedroom.

‘Who the fuck is she?’

She’s flushed, breathing hard.

‘Jesus Parks. She needs a pass, that’s all. I thought you might be able to help.’

‘And what’s she giving you?’

He shakes his head, tutting disappointment.

‘I told you to call me Rasheda anyway.’

‘Do you have them? Please.’

Her chest heaves. Geoff keeps his eyes on her face. He tries to push away his memory of how she looked in dim light, unclothed beneath his faded bed sheets.

‘Please Rasheda.’

She sags again, and he feels bad. He’d thought her tougher than this. Tonight he sees she actually cares, only it’s too late.

‘I’ve only got the one anyway.’

Geoff hears birds, the engine thrum of the bendy bus.

‘What?’

She stares into his eyes, not letting go.

‘Obviously they know my circumstances. Some of the guys needed more, what could I say? You’re lucky they gave me this.’

Rasheda holds an orange envelope, tilting it at him.

‘Good thing too. Considering.’

‘I’m not sleeping with her.’

‘That’s not my business,’ she says, looking at his unmade bed, the scattered books, papers and clothes, the undrawn curtains. ‘You can do what you like. Can’t you?’

The muscles of her jaw protrude. She looks at the window.

‘This is just silly.’

‘D’you think?’

‘Don’t you?’

She stares him down. He drops his gaze, grits his teeth.

‘Will I see you in London?’

He knows the answer, yet Rasheda has grace enough to smile. She gives him the envelope.

‘Probably not.’

She leaves then, softly closing the door.

He gathers the important things in a rucksack. Laptop, novel, notepad. He tucks the flimsy pass into an old Oyster wallet, pockets both and puts the orange envelope face up on the coffee table with Nuria’s name printed in black felt tip. He hasn’t told her much. Just that the flat’s hers if she wants it, that he had to leave immediately, where the folder is with information about the boiler and all other household appliances. He hasn’t said he’s sorry. He wants to, only he doesn’t know how to word it, everything he writes feels wrong. Geoff feels his hands tremble and tightens them into fists. He puts his house keys on top of the envelope, slipping out before Nadia wakes to find him standing over her, the difference between them alive and naked in his eyes.

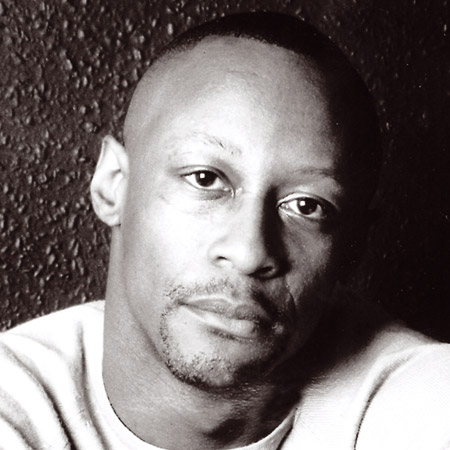

Courttia Newland

Out of the box, inner city, stylistically diverse, musically influenced

SEE PROFILE