A provocation? How about, instead, a confession: I’m not sure I like literature festivals.

Never mind I help run one — the NGC Bocas Lit Fest, here in Trinidad and Tobago, the biggest literature festival in the Anglophone Caribbean. Never mind the uncountable hours I spend putting together an annual five-day programme, dealing with something like a hundred writers, speakers, and performers, devising them into readings and discussion panels, sorting out their various logistics, drafting programme copy and press releases, introducing writers to audiences, escorting them on and off stages — not to mention fetching them cups of tea or replacement pens, calling for taxis, making phone calls about misplaced passports, rearranging chairs, and the numerous other small tasks that allow the show to go on.

Whatever literature is — and I strain for the broadest possible definition — I swear allegiance to it.

Never mind, either, that I can, will, and must make a forceful argument for the value of a festival like Bocas, and our other year-round programmes, to writers, readers, publishers, and everyone else with a stake in the business of literature. Or that I’m fiercely proud of the work my colleagues and I have done since Bocas launched in 2011, especially our work with new and budding writers, whose success we can now tangibly tally in books published and prizes won.

My confession is a contradiction, perhaps a conundrum, but I hope not a total hypocrisy. Whatever literature is — and I strain for the broadest possible definition — I swear allegiance to it. For most of my life, reading has given me more pleasure, more consolation, more stimulation than any other activity. I live surrounded by thousands of books, a proliferating profusion, more than I can read in my lifetime. There are too many of them, and I can’t get enough of them. I’m a writer myself. It is a life sentence I have no wish to appeal.

My confession is a contradiction, perhaps a conundrum, but I hope not a total hypocrisy. Whatever literature is — and I strain for the broadest possible definition — I swear allegiance to it. For most of my life, reading has given me more pleasure, more consolation, more stimulation than any other activity. I live surrounded by thousands of books, a proliferating profusion, more than I can read in my lifetime. There are too many of them, and I can’t get enough of them. I’m a writer myself. It is a life sentence I have no wish to appeal.

But, but, and but: there is something about the packaging of literature as public entertainment that irks me, often unsatisfies me, even bores me. As a reader, what I crave is that particular delicious solitude that only immersion in a book can create — a physical solitude that is at the same time an intellectual and emotional communing across time and space. And as a writer, I am slightly mortified by the public performance of authorhood, so self-conscious and stagey. The best experience of literature, for me, is quiet, private, and involves reading propped up in bed or writing at my own desk at home, the door closed.

Yet and yet: I do know that literature has a millennia-old tradition of communal and public performance. I know that, especially in the Caribbean — where access to formal education was long determined by social class, where literacy levels are still relatively low, and the availability of books relatively unequal — oral and performance traditions greatly expand literature’s possible audiences. Trinidad and Tobago is a small nation of one and one-third million, divided between two islands, with only a half-handful of decent bookshops, a publishing industry so fledgling it is barely out of the egg, and scant attention to books in the press. And then there’s us at the Bocas Lit Fest, and those uncountable hours we spend searching out new literary talent, corralling an audience, bringing together writers of the sizeable Caribbean diaspora with their peers at home, taking writers to schools and libraries, organising workshops, lobbying the media for literary coverage, and generally making a space — a growing space — for something like a national conversation about why literature matters, and to everyone.

Because in a small place sometimes you have to do it all yourself. There isn’t the critical mass that might allow certain kinds of specialisation. So Bocas has never been merely a literature festival, an occasion for the leisurely bookish to hobnob. We knew from the beginning we’d have to be more — have to be, sort of, everything: not just impresarios and stage managers of literary entertainment, but talent-spotters, agents, editors, critics, teachers, publicists, philanthropists, ambassadors, apostles. We have become, in fact, a sort of unofficial Ministry of Literature. The free five-day festival in Port of Spain — along with the two smaller regional festivals we run each year, in south Trinidad and in Tobago — is the most public aspect of our work. But I sometimes think it’s not necessarily the most important.

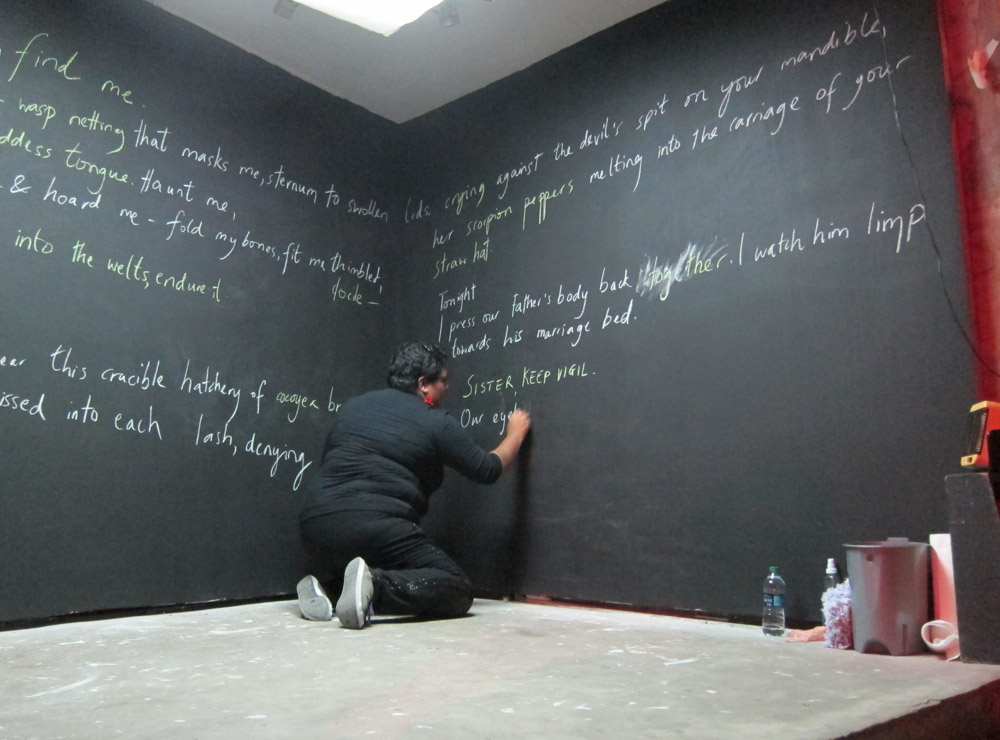

Shivanee Ramlochan never says a word: instead, chalk in hand, she writes her thorn-bristling poem in slanting lines across the walls of a black-painted room

Still and still: how do I reconcile all this with my original confession: my dislike of literature festivals, or at least of their showbiz face? Simply by remembering that I’m not programming a festival just for myself. Once again, in a small place I don’t have that luxury. If there can be only one literature festival in Trinidad and Tobago — which is one more than some other Caribbean islands have — then it must be a festival for everyone. That’s what an allegiance to literature demands. So, yes: let’s have readings where poets can declaim, debates where novelists can square off with historians, lectures by neuroscientists and economists. Let’s have a national spoken word slam where young performers are greeted like rockstars. Let’s have storytellers and magicians for children. Let’s have calypsonians duelling in risqué extemporised lyrics. Let’s have writing of all genres, writers at all levels of achievement: a Man Booker Prizewinner on this stage and an absurdly diverse open mic on that one. Some of this will make me roll my eyes, some of this will make me pout, some of this will make me bite my tongue.

But some of it will make me smile or ponder, and some of it, surely, will cut me to the quick. Because whatever I may dislike about festivals, the literature itself — and what happens when someone truly encounters a poem, a story, an idea bound into words and unbound into the world — is the pure seam somewhere inside the rubble. And despite myself, despite my impatience and self-consciousness, there are moments of revelation. Here are three that refuse to fade in my memory.

One: at an event celebrating the legacy of the late poet Martin Carter, my friend Vahni Capildeo, after reading a couple of her own bracing poems, turns to Carter’s “After One Year”. It is a poem I have read many times, and thought I knew well. As Vahni pronounces each line with a terrible, calm clarity, I realise now I am knowing Carter’s poem for the first time. By the end of the second stanza, I have all but lost my composure.

Two: In Forests & Wild Skies, an evening of words, music, and images created by a small collaborative called Douen Islands. The courtyard of the arts space Alice Yard is transformed into something eerie and otherworldly: bathed in red light, dead leaves everywhere, shin-deep. The poet Andre Bagoo recites his poems while performing a shadow-play behind a screen. The fiction writer Sharon Millar announces her sinister tale with the ringing of a handbell. And the poet Shivanee Ramlochan never says a word: instead, chalk in hand, she writes her thorn-bristling poem in slanting lines across the walls of a black-painted room, contorting herself into a crouch to get its last phrases into the most remote corner. It is agonising to watch her, and spellbinding to wait for the words to become legible.

Three: a Saturday afternoon session at the festival, co-hosted by the Adult Literacy Tutors Association. An assortment of ALTA students — grown women and men with the courage to admit they could not read, and do something about it — have composed short narratives of their lives with the help of their tutors, and now they are here to share them, to read in public for the first time. The audience is crammed with family, friends, ordinary festival attendees. A gentleman in his eighties comes up to the microphone. Voice wavering, he begins to read his brief account, ending with his gratitude for the chance near the end of a long life to acquire this gift that I myself take for granted. In the front row, his children and grandchildren smile at him through tears. There are few dry eyes, indeed, in the audience of one hundred. A reading by a Nobel laureate could not feel more overwhelming, more important.

It wouldn’t be quite true to say that at these moments my irritations with the business of festivals are soothed to rest. If I’ve taken nothing else from books, I’ve learned how to find balance in a tension of contradictions. So I may sigh and fret and long for the seclusion of book and bed and door closed against the rabblesome world. And at the same moment feel gratified to help make these occasions for those who love literature in its other forms: loud and lively, sociable and crowded. The words are what matter, whether cherished on the page or on the stage — or in any other place where literature thrives and provokes.

Nicholas Laughlin

Programme director, Bocas Lit Fest

SEE PROFILE

My confession is a contradiction, perhaps a conundrum, but I hope not a total hypocrisy. Whatever literature is — and I strain for the broadest possible definition — I swear allegiance to it. For most of my life, reading has given me more pleasure, more consolation, more stimulation than any other activity. I live surrounded by thousands of books, a proliferating profusion, more than I can read in my lifetime. There are too many of them, and I can’t get enough of them.

My confession is a contradiction, perhaps a conundrum, but I hope not a total hypocrisy. Whatever literature is — and I strain for the broadest possible definition — I swear allegiance to it. For most of my life, reading has given me more pleasure, more consolation, more stimulation than any other activity. I live surrounded by thousands of books, a proliferating profusion, more than I can read in my lifetime. There are too many of them, and I can’t get enough of them.