This piece was commissioned by the ILS as part of the 'Crossing Borders' series.

An April bank holiday Monday, and I plan to go across the border somewhere in the south-west of England. I don’t know the exact place, but between Newbury and Bath the Kennet and Avon canal stretches fifty-odd miles over the English countryside. My border point will be the 60 foot narrowboat Eve, which has a continuous cruising licence, meaning that every fortnight it has to move. My friend Drusilla Marland, who lives on Eve, is hard to pin down.

I find Eve moored tight to the towpath near the wharf in the Wiltshire town of Devizes. The sun is out though the wind is chill; Dru’s boat is magnificently ugly.

‘Skanky boat,’ Dru had said. ‘Social misfit, bicycles and firewood on top.’

The live-aboards, the continuous cruisers, are sometimes known as ditch-gypsies. They have no permanent mooring, or cosy winter berth in a marina. ‘Asylum seekers, terrorists, narrow-boaters,’ Dru warned me in advance. ‘We’re bottom of the heap.’

The roof of her dark green boat is a rusting ecosystem of bike-frames and rough-cut branches. Also a bicycle trailer and a crumpled blue tarpaulin and multiple brooms and boathooks. If I look very carefully, I can tell the roof was once painted orange.

Whatever else, Eve is evidently home to a form of life. She is inhabited.

Out on the footpath Dru is dressed in loose autumnal russets, matching the copper-red of her hair. We embrace, and she smells of coalsmoke and corduroy, of a night’s warmth trapped in the heavy wool of a cardigan. Dru stands back. She is tanned, four-square, hungry.

‘Bacon sandwich? Come on board.’

This is it. Like mayflies, the employed and the landlocked can flit through entire lives in a single day. We can use bank holidays to escape across the border, any border, where we try out someone else’s experience of what living might mean.

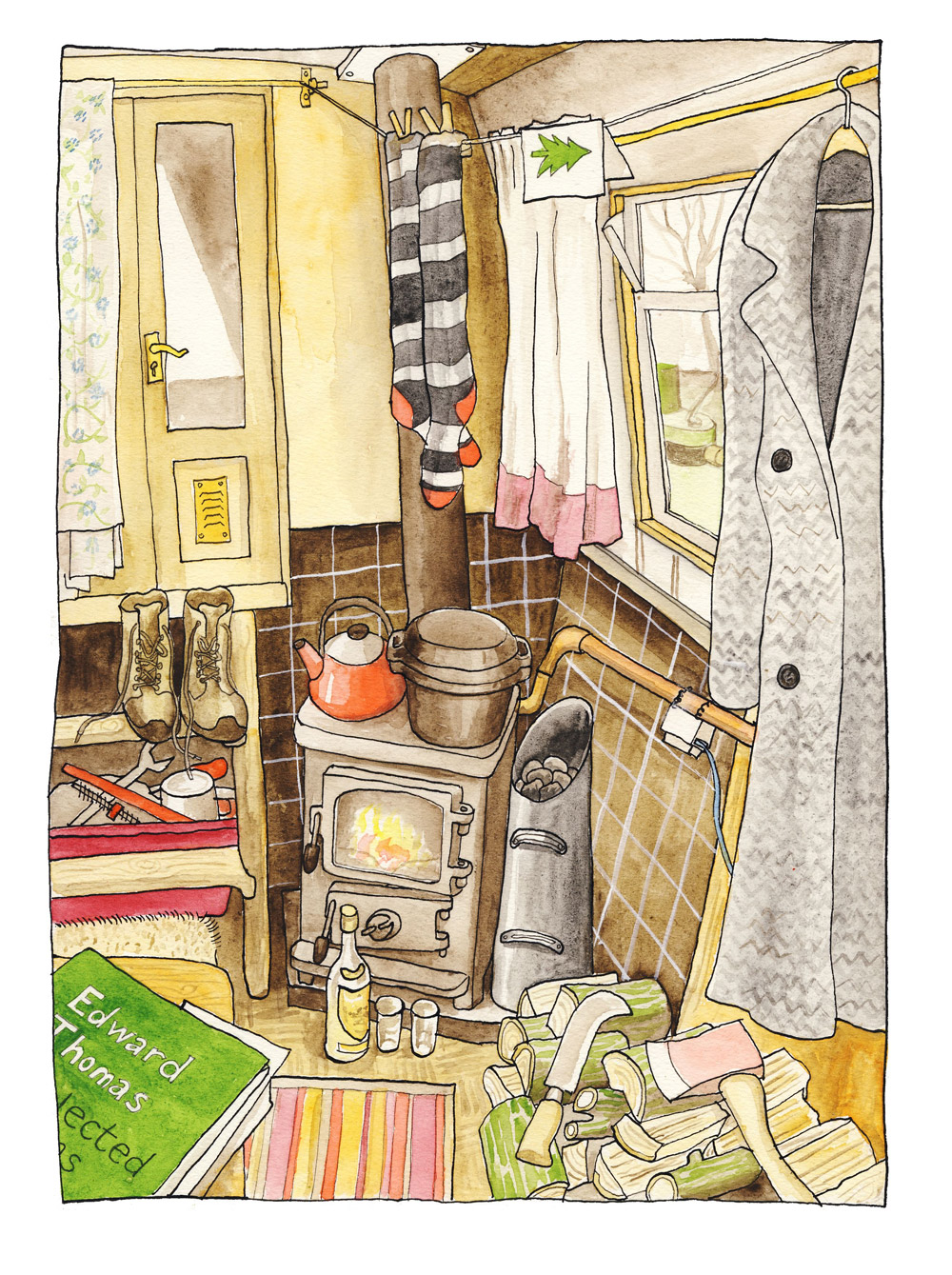

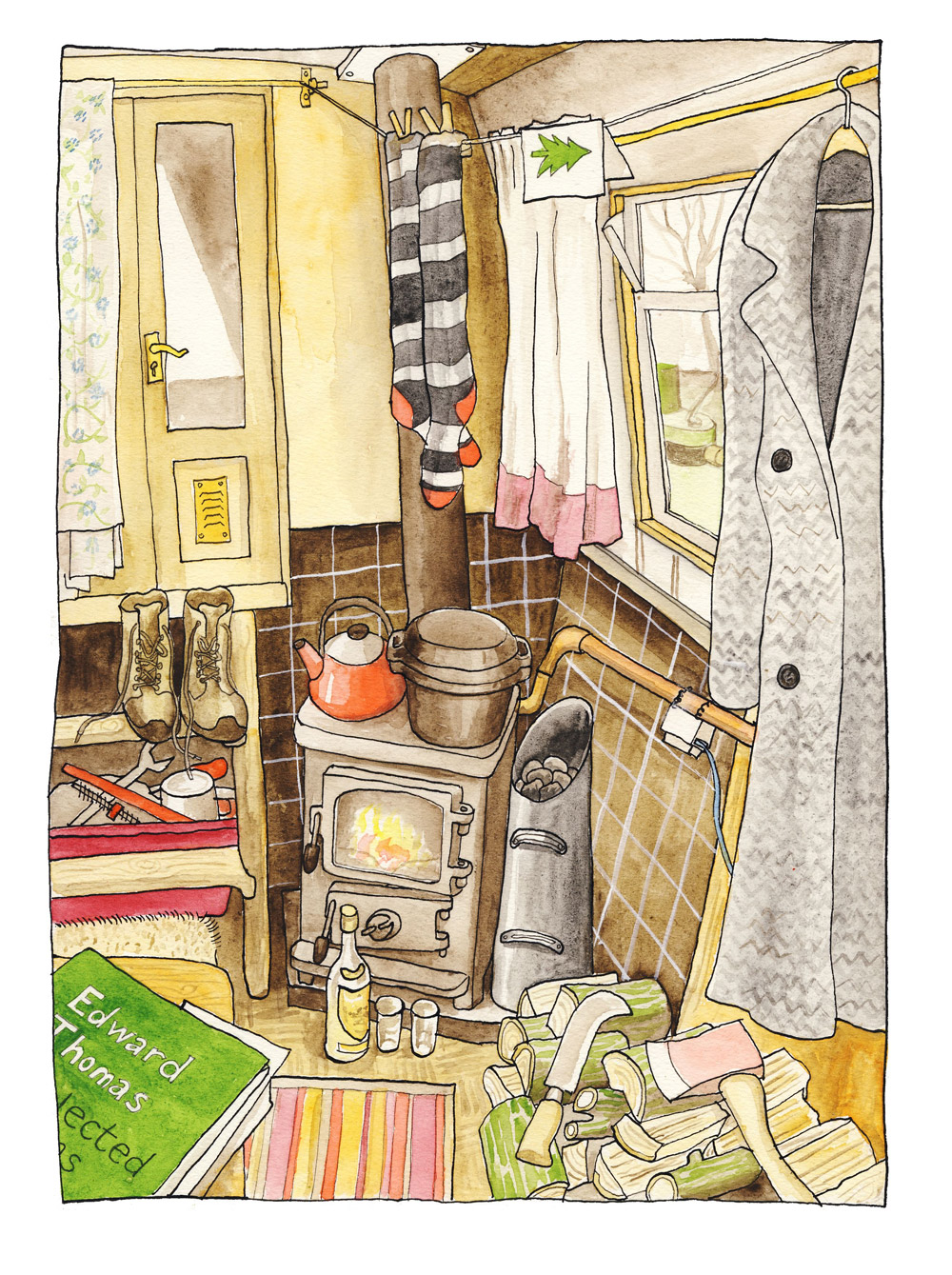

Without special ceremony, I step into the open bow of the narrowboat, a storage space for buckets and bags of coal and rope. I bend double and follow Dru through the low double doors and down below the water line. That’s as far as I can get. Dru expertly navigates along the narrowness of the boat to the galley, but I stay where I am by the wood burner, blocked by an extravagant mess.

I can’t say I’m surprised. Once upon a time, a long time ago, Dru lived in a flat on solid ground, and when I wanted to describe her living space I approached the task like a naturalist. I took a random square-metre of kitchen table as representative of the whole, and was able to draw up a half-page list that numbered forty-one separate objects. These included a jar of Italian pickled onions, a roll of pressure-sensitive industrial duct tape, a beret and a cat.

Eve is filled with the same unrelenting clutter, minus the cat.

‘Ah yes,’ Dru says, looking around with an as-if-for-the-first-time gaze, a gift that only judgmental visitors can bring. ‘My spring-cleaning.’

‘Good luck with that.’

‘I’ve already started.’

The bacon sizzles, the kettle on the gas stove boils.

‘I need less stuff,’ Dru finally decides.

‘You don’t say.’

‘But then I do so much stuff. I need the stuff for the stuff.’

I avoid stepping on a De Walt drill that’s propping up a brass hunting horn, and at random I pick up a metal rod.

‘Studbar,’ Dru says. ‘Useful for things.’ She looks around again. ‘There used to be a chair in here.’

I sit on the wooden steps beneath the bow doors, comfortable in the pleasantly coal-warmed boat. Tea brewing, bacon ready, Dru inspects the end of a huge white loaf, of the type they sleep on in heaven. A black beetle is investigating the crust, and Dru inspects it with care because curiosity, in this life I envy, reliably outranks hygiene.

‘It’s an ash bark beetle,’ Dru says, and dusts it away.

‘Do they like bread?’

‘No, they like ash bark.’

Ash is the best firewood, and plenty of inoffensive beetles live happily enough on the roof. They come inside with the logs.

We chomp away contentedly at our huge white sandwiches, then step out into the sunshine to explore this week’s neighbourhood. We don’t get far before Dru insists we stop. In the hedge beside the towpath a bird is trilling. Dru cocks an ear and identifies ‘a blackcap with a lot to say for itself’. She points out a nest of young robins, and lines up a photo with her high-powered camera, always at the ready in its case around her neck. We wander as far as the Caen Flight, a man-made wonder of 29 closely-spaced locks that drop the canal 72 metres down a steep green hillside. Dru snaps away at birds and insects, and on hands and knees she shows me viper’s bugloss and cuckoo flowers. We climb across the gates of a closed lock (steadily, in my case, because it’s not something I do every day) to examine up close the orange blaze of a clump of marsh marigolds. Dru also points out the bush where a flasher sometimes lurks. That’s a type of person, not a bird.

Because the canal has a double life. On a bright bank holiday towards noon this is a recreational space that accommodates families and dogs and cyclists. Hire boats chug up and down, occasionally under control. A waterside pub has a garden with picnic tables and moorings for thirsty daytrippers.

But on greyer days or at night, not just here but throughout the UK canal system, the towpath becomes a transitional space, somewhere between normal and not. It’s where people come to weep, to lug furniture into the water, to scream out loud and slug on tins of Polish lager. The canal is a border for people who don’t know where they belong, neither here nor there, one thing nor another. It’s the end of the road, and a possible escape route.

And yet. When the sun is out, a shiny vintage car will toot as it jaunts over Devizes bridge. Dru misses it, and I don’t know the make, but the car was polished to a high black shine that splintered the afternoon sunlight.

This is more the kind of vision that postwar champions of the canals had in mind, not least because they were thinking their thoughts in 1959. That was the year of the founding of the Inland Waterways Redevelopment Committee, which had the noble aim of reinventing disused canals as viable public space. It’s unlikely they would have had Dru in mind as a beneficiary - the continuous cruising licence was only added to the British Waterways Act in 1995. Before then, neither the law nor canal-lovers had imagined anyone wanting to live on a narrowboat all the time, the long year round.

The British Waterways Act prevents anarchy on the Kennet and Avon. There are rules, quite a lot of them. The annual continuous cruiser licence costs £800, and requires live-aboard boaters to be ‘engaged in meaningful navigation’. This means observable progress from A to B to C. No short hops from A to B then back again, not in this jurisdiction. Anyone found standing still risks a warning notice from a Canal and River Trust volunteer, and in extreme cases the dreaded Section 8 will be served – a boat to be removed from the water.

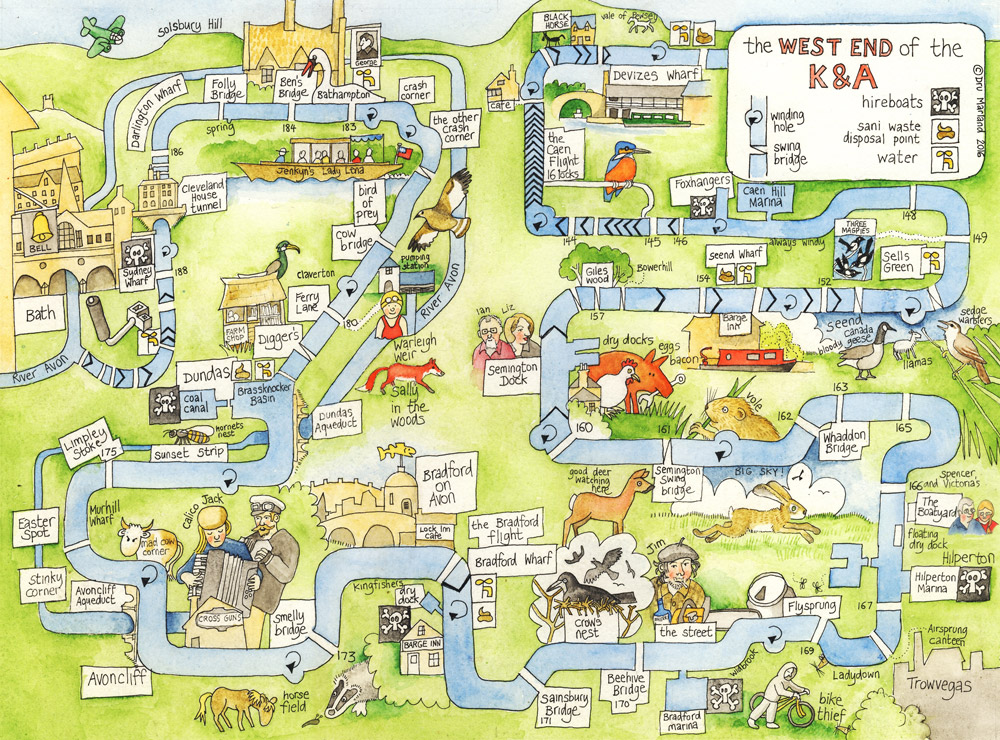

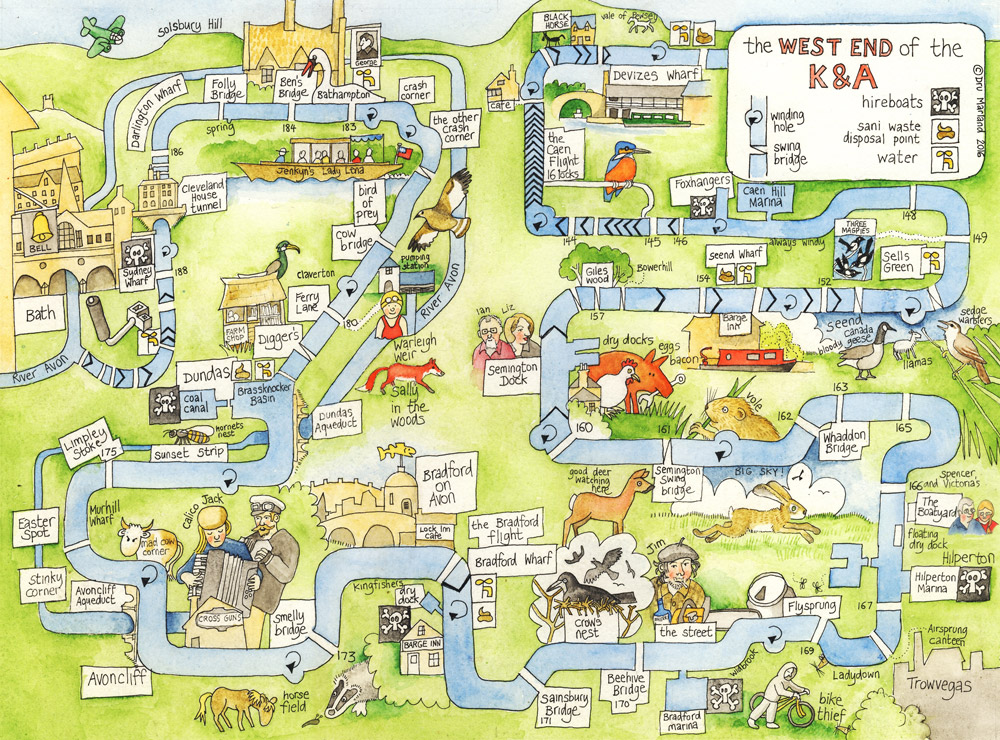

Click here for large version.

Dru gets extra perks by having a trading licence. She sells her artwork, and her current bestseller is an illustrated map of the canal’s West End from here down to Bath. The map features unofficial but instructive place-names, like ‘smelly bridge’ and ‘crash corner’ (not very far from ‘the other crash corner’). As a trader, Dru can stay a little longer at busy spots like Devizes during peak trading times, such as bank holidays. The boat moored next to Eve makes fabulous leather bags. Further down they’re selling knitted dolls and children’s sweaters. No one will make a fortune like this, but no one needs a fortune – we estimate that Dru’s annual costs on the canal, inclusive, rarely exceed £6000.

‘The canal is a long thin village,’ Dru says. She knows most of the boats and many of the boaters by name. A few are ‘rogues but not crooks’, a tolerant view that serves well because rogues and crooks would like it to be true. As for rogueish mishaps, the police are rarely invited to intervene – no one wants to tell tales (not off the canal, anyway), and in past lives the boaters may have found the police less than helpful.

‘We have quite a few ex-Convoy types,’ says Dru, meaning the New Age travellers whose converted lorries and buses scared the heart out of Middle England in the 1980s. Live-aboard boaters sometimes experience a similar level of prejudice – accused of ruining the classic picture of the English picturesque, and emptying their shit canisters into the bushes.

‘Which we don’t do,’ Dru says emphatically.

Continuous cruisers suffer from the worldwide disease of ‘othering’, which seems always to be spreading, like an unstoppable blight through a once-loved species of native tree. The boaters are ‘others’ across a man-made border, beyond the pale. A free-living, floating community is another outbreak of diversity to be distrusted and disempowered.

And across this border, the waterborne refugees aren’t themselves immune from the lure of outsider glamour. Boaters too can define themselves by a false idea of what they’re not, and their landlord the Canal and River Trust may not be the evil organisation that some are keen to demonise. Section 8s are a last resort, and the CRT acknowledges special circumstances. Sick and pregnant boaters are given dispensations to stay in a single place.

In return, the continuous cruisers should be given credit for re-purposing the canal. In that sense they’re the future, where we’ll constantly need new uses for whatever remains to us, whether excess plastics or redundant infrastructure. It’s no wonder, then, that Dru’s life on Eve can seem at the same time pre-industrial and post-apocalyptic. The problems and solutions look similar.

On this one day along the canal, I continuously see a living community in action. We lift a couple of folding chairs off the roof and sit on the towpath grass with mugs of tea; people stop for help or a chat. A man carrying a Chihuahua speaks at some length and incomprehensibly about Moulton 4-speed gearboxes. Over the border they speak a different language, and it’s only later I spot a fading sign on Eve’s roof from one of Dru’s earlier trading ventures:

Poetry, art and bike repairs. Ici on parle Sturmey Archer

I find I can still get by, just about, with English. Dru fixes a bike (‘Oh, I didn’t mean now,’ the owner lies). She lends a bilge pump to a huge gut of a man wearing a T-shirt that says Body of a God (shame it’s Buddha), who has managed to spill 80 litres of diesel into the hull of his boat. Under the circumstances, Big Tony decides not to patronize his mechanical saviour, even though she’s wearing a dress.

Other souls with lives strung out along the canal stop to talk. Sometimes this means conversation, but more often they want to offload a story – that’s what a familiar face is for. Late in the day, after a quick pint of 6X in the Black Swan, Dru coordinates the finding of a lost dog using only a Facebook page, Sherry Jim’s phone and some ancient towpath magic I don’t fully understand. Another day in the life of the cut: we welcome the dusk with cans of lager, eat white bean and sausage stew, respect the local customs.

Then comes the night, every night, and the fear with the going down of the sun. As I step gingerly through the boat I see a thousand potential accidents: falling, breaking, cutting. My bunk is at the stern, beyond the tubular mass of green and brass engine. While Dru clears the bottom berth of clothes and tools, I ask her if she ever worries about leaks.

‘I mean sinking. Are you frightened of sinking in the night?’

Dru says it’s unlikely, and anyway, at our present mooring the canal is shallow. We’d have enough airspace up near the ceiling to breathe.

‘You’ve thought it through then. What about accidents? Aren’t you afraid of hurting yourself, a long way from professional help?’

‘Not really,’ Dru says. ‘No. Except when I fell in the lock.’

In three years, Dru has fallen into the water three times.

‘It’s much harder to get out than to fall in,’ she says.

And that’s really what I mean by the fear. I could fall into this life, but could I ever get out again? Dru tells me of a fire on a boat near Bradford on Avon. It can happen, because the canal offers refuge to men of a certain age, after divorce, who drink too much. I recognize the direction of travel – over the fence, under the wire, across the border to an altered future.

‘The man was burned alive,’ Dru says. ‘Fire is a serious danger.’

If not water, then fire. Freedom comes with risk. Also possible carbon monoxide poisoning, from the woodburner. On the canal half the elements want to kill you, and some of the compounds, too.

‘Don’t worry,’ Dru says. ‘I always make sure the emergency exit is clear.’

It’s true. The stern doors beside my bunk are clear, but in the non-emergency direction I’ll be sleeping with two petrol cans, a generator and a pair of gold 14-hole Doc Martens.

But genuinely I have nothing to fear, because beneath my bed there’s a chainsaw. The temperature dips at night, so Dru has given me three sleeping bags that together are good for 10 seasons of weather protection. I curl up underneath, inside. I’m in a burrow, in the dark, a sudden version of comfort and home.

Eve rocks as Dru potters about before turning in. Then the boat steadies and is quiet with the total absence, all but forgotten on land, of passing cars. There would be no going back. The economics of narrow-boating make it an expensive hobby but a cheap way to live, which for continuous cruisers means a one-way ticket across the border – coming back over would lead to rent payments, a regular job, the familiar sinking. I drift off thinking of the ‘others’ along the canal and the ‘others’ up on the bank. I’m on Dru’s boat which floats on someone else’s water. We all need each other.

Morning comes, first light grey in the single porthole. Eve is still afloat, and the outside quiet is tested by early arrivals for the dawn chorus, then a duck frisks its wings against the hull. My phone says the outside temperature is 3 degrees. I’ve shed six of the ten seasons, but after a single night the boat already feels like home.

Then it starts to rock, because Dru is up and about. I pick my way towards the galley and the fire, stopping by the opened hatch directly opposite the engine. Up to my waist in water I have a redbrick view of the Wadworth brewery opposite, blue 6X flag flying, and in the brown canal beneath me blossom drifts by. Even on the cut there is a constant slow shifting. The water moves when someone operates a lock, or when pumps maintained by the CRT push water back uphill to counter the drop of the Caen flight. Nowhere stands entirely still, or is immune to events elsewhere.

Outside, in the border territory of the dawn, we can tell who’s awake along the glassy cut, from the chimneys. Woodsmoke, coalsmoke. I register brown birds, green plants. In this new country I’m still not sure what I’m seeing.

Dru does her pre-engine check, which includes moving items off the engine. I get ready to cast off from the bow. Devizes is at the western tip of the long pound, and eastwards from here we have fifteen miles without locks through the Wiltshire flatlands. We can head towards Hungerford at four miles an hour, engaged in genuine navigation. It’s April now, and Dru has somewhere she’d like to be by late July. Taking the long way round she hopes to see otters, and tonight, in the Vale of Pewsey near Bishops Cannings, she’ll set her crayfish trap. The canal is another country. They do things differently there.

Images (c) Dru Marland

Richard will be appearing with Max Porter and Cathy Rentzenbrink as part of the City of Literature programme at the Norfolk & Norwich Festival in May 2017.

Friday 26 May, 2 - 3pm

Adnams Spiegeltent, Chapelfield Gardens, Norwich

Tickets £8

Richard Beard

Curious, experimental, mashed-up

SEE PROFILE