Part of the ILS' 'Crossing Borders' series.

I’ve always been a nervous flier. I'm writing this having landed less than an hour ago on the island of Roatan aboard a Jetstream 31, a plane so small that when a member of the airport's ground team pointed it out to us saying we should board 'El avión blanco' I hoped he was mistaken. For the benefit of those like me who are, at best, ambivalent about flying let this suffice: it was bumpy and we felt everything. The flight was from Tegucigalpa where I'd been co-facilitating a workshop for young Honduran poets on a project jointly run by PEN International and Roundhouse London. When I speak such sentences aloud, my life sounds quite apart from anything I could have imagined.

One of my favourite songs, 'You Got Me' by The Roots, contains the line 'I'm the type that's always catching a flight' and lately it certainly feels that way. I've been in Austria and Sweden and Honduras in the space of eight weeks with further trips planned in the next six months, all these trips paid for by someone else. Poetry is my passport. More often than not, when I travel, it is because I decided to be a writer some time in my childhood and have held fast to that decision ever since. But how did a boy from the copperbelt in Zambia, son of an engineer and a drug researcher, come to be a poet, of all things? This is the precise question my uncle Chivanda, affectionately known as Ba B, asked me when I was in Zambia in January. It was the first time I had been back in almost 25 years.

My ambivalence to flight started somewhere 'above the weather', as the poet Dai George would have it, aboard an Aeroflot flight from Lusaka to Gatwick (via Moscow). It was 1993. My mum was taking me to live with her in the UK where she was studying to be a librarian, having previously worked in the British Council Library in Ndola. The journey was going well from my perspective, not least because the flight attendants kept bringing us delicious food. It was only as we hit turbulence that I started having misgivings. Hitherto unconsidered thoughts became loud voices in my head shouting 'What's to stop this metal box falling out of the sky?' and 'Are we all going to die and go wherever dad went when he died a few weeks ago?'

Image: Kayo, aged six, with his mother at his father's grave

For most of my life I have explained the context for my leaving Zambia by saying that when I was six years old my dad died and my mum, who was living in the UK for her studies, came and got me. What I usually leave out is that I can't be sure whether my parents were estranged or broken up at that point. All that I know is that I don't have a picture of them together, in my head or anywhere else. I don't remember this but have been told that when my dad died there was disagreement as to whom I should live with. While my mum was in the UK I was mostly looked after by my Dad's family, a procession of aunts and uncles and cousins who call me by my full name, Kayombo, because this name is the name of my father's father Smarts Kayombo Chingonyi and the name of Mr Yonga, brother to my father's mother. It is, in short, a name that identifies me as Luvale, a tribe from the North West of Zambia with roots extending to Angola.

As a result of the disagreements that followed my dad's passing, I became disconnected from the Luvale part of myself and from the country I had always known. Until January of this year I had not seen or spoken at length to anyone from my Dad's side of the family since I left in 1993. So deeply was our estrangement entrenched that most of my family on that side tell me they had given up hope of ever seeing me again. For my part, I had been wanting to make contact for years but the mysteries of my departure meant that I wasn't sure how I would be received.

Image: Kayo's father's three siblings (L-R): Uncle B, Uncle Titus and Uncle Rodgers

Poetry is one of the reasons I am now in contact with my family again. The fact that my readings have been recorded and posted online, that I have a website and social media profiles, means that I can be found. Some while back one of my uncles managed to reach me through an online directory of poets and we spoke briefly. He asked me to call back, and when I did, the call didn't go through. Later my cousin contacted me via Twitter. The family had been trying to get in touch with me. My grandmother had died the previous year and I didn't know. My cousin told me Kakha, the Luvale word for a Grandparent, kept a picture of me next to her television and spoke about me to the cousins born after I left. She had taken the sofas from the house I lived in with my dad and was keeping them for me until I came back to claim them. Finding out about Kakha's passing showed me how disconnected I was and I resolved to save some money for flights and go back. The feeling of disconnection wasn't new but this was the first time I realized what damage it had done. It took me over a year but through working on poetry projects I made enough money for the flights and wended my way to Gatwick to board a Boeing 777, a reassuringly vast aircraft, bound for Lusaka (via Dubai).

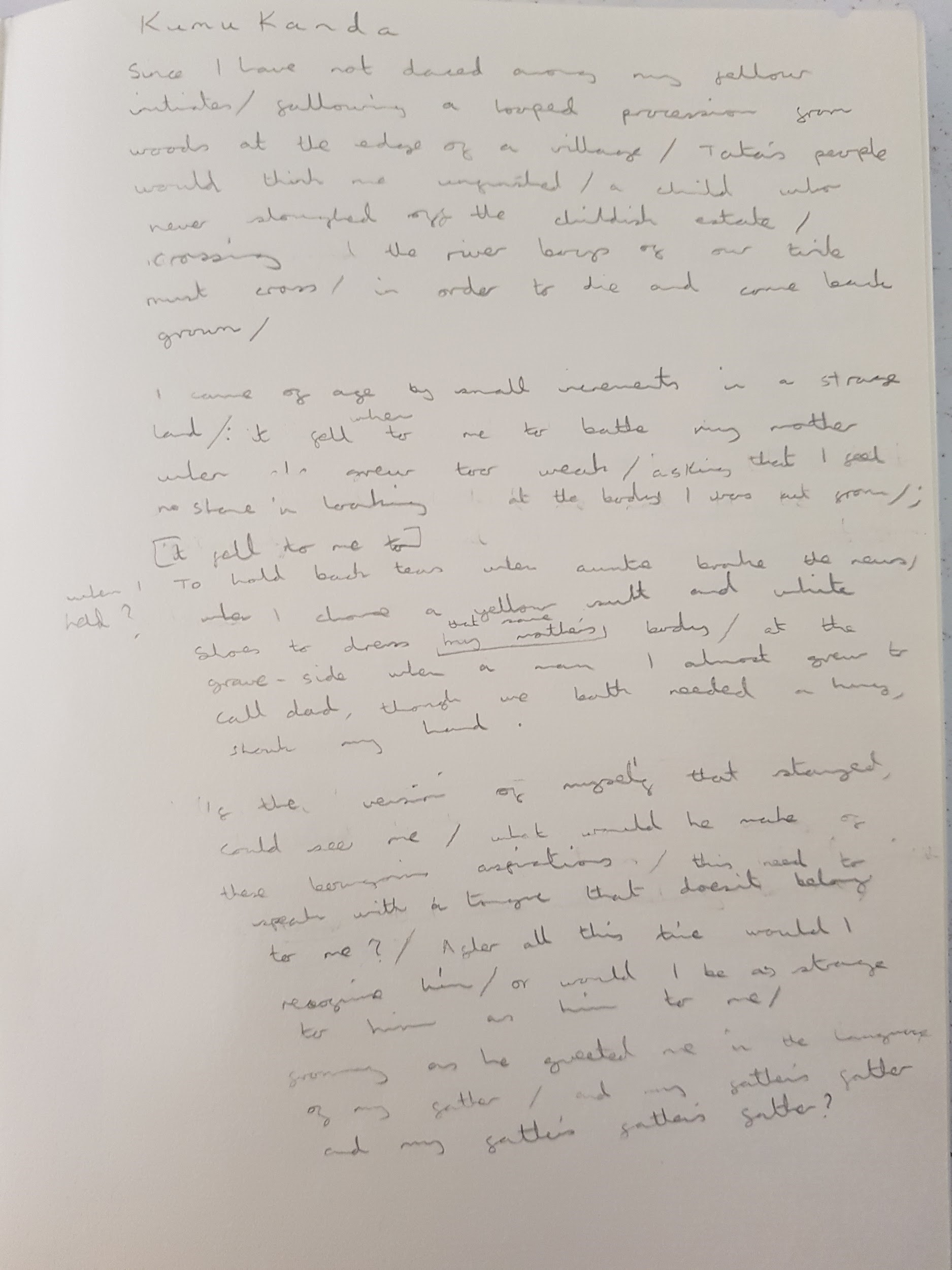

The feeling of disconnection is how I exist in the world as someone who both is and is not British. To be both British and Zambian is to be neither one nor the other. It is a hybrid way of being that means I can't be accepted by either 'side'. In the space of the poem, though, I can be both. I can write in English about my Luvale heritage. I can incorporate phrases from Bemba and Luvale, making a new English to add to the various Englishes that already exist. This notion of the poem as a space in which I can exist in my fullness is probably why I have chosen poetry as my medium. What is a poem but a record of something the poet cannot get past? A memory, an impression, a phrase, some musical quirk of language? These are the questions behind most of my poems and certainly haunt the poem I have found most difficult to write, the title poem of my first full-length collection, Kumukanda. A poem that, in some respects, I have been trying to write since I first started writing poetry in earnest when I was thirteen. I present here an early draft of the poem, handwritten while I was in Zambia, and the poem as it appears in Kumukanda (Chatto & Windus, 2017).

Kumukanda

Since I haven’t danced among my fellow initiates,

following a looped procession from woods at the edge

of a village, Tata’s people would think me unfinished —

a child who never sloughed off the childish estate

to cross the river boys of our tribe must cross

in order to die and come back grown.

I was raised in a strange land, by small increments:

when I bathed my mother the days she was too weak,

when auntie broke the news and I chose a yellow suit

and white shoes to dress my mother’s body,

at the grave-side when the man I almost grew to call

dad, though we both needed a hug, shook my hand.

If my alternate self, who never left, could see me

what would he make of these literary pretensions,

this need to speak with a tongue that isn’t mine?

Would he be strange to me as I to him, frowning

as he greets me in the language of my father

and my father’s father and my father’s father’s father?

Kayo Chingonyi

Lyric poet with a passion for music

SEE PROFILE