When most people hear the term ‘live literature’ they often visualise two very different types of event.

One is the literary festival, where audiences gather to hear authors talk about their new novels, read short passages aloud, answer questions, then sign books sold in the shop afterwards. They sometimes leave with an impression that the whole event might have been an extended sales pitch.

The other is the spoken word scene, where poets tend to perform in informal urban settings like bars, usually on their feet, without a text – the text often being unpublished – using a high rhetorical delivery style, and rarely engaging in Q&A. Audiences are often practitioners themselves, and open mic is a common format.

A perceived chasm lies between the two. The latter, by being more inherently performative, clearly places more emphasis on ‘liveness’. It places more emphasis on literature too, in the absence of Q&A, but is still often fairly predictable in format and delivery.

So how can we inject more liveness and literature into the live literature scene, particularly for fiction? How can we expand the perceived scope, richness and diversity of ‘live literature’ as an art form?

The truth is that there are plenty of variants of events within the umbrella of ‘live literature’ that present fiction in a more performative way than the mainstream festival. I’ve discovered several in the course of my PhD research. There are literary club nights, salons and death matches, and there are story and book slams, all of which shake up the vibes, venues and audience demographics as well as formats.

But there is still scope for more. In particular, there is potential for more events presenting fiction that prioritise both the literary text and the liveness, and that dare to push against perceived genre boundaries to make something new and engaging for audiences, that will lead those audiences to experience and think about and value the texts in new ways. For interested writers/performers/producers, there are plenty of lessons that can be learned, not just from the performance poetry scene, but from the worlds of theatre and live art, where performance is valued much more highly, and spatial, visual and aesthetic considerations are given more weight in relation to the text.

These motivations were what led me – somewhat rashly – to set up my own experimental live literature project.

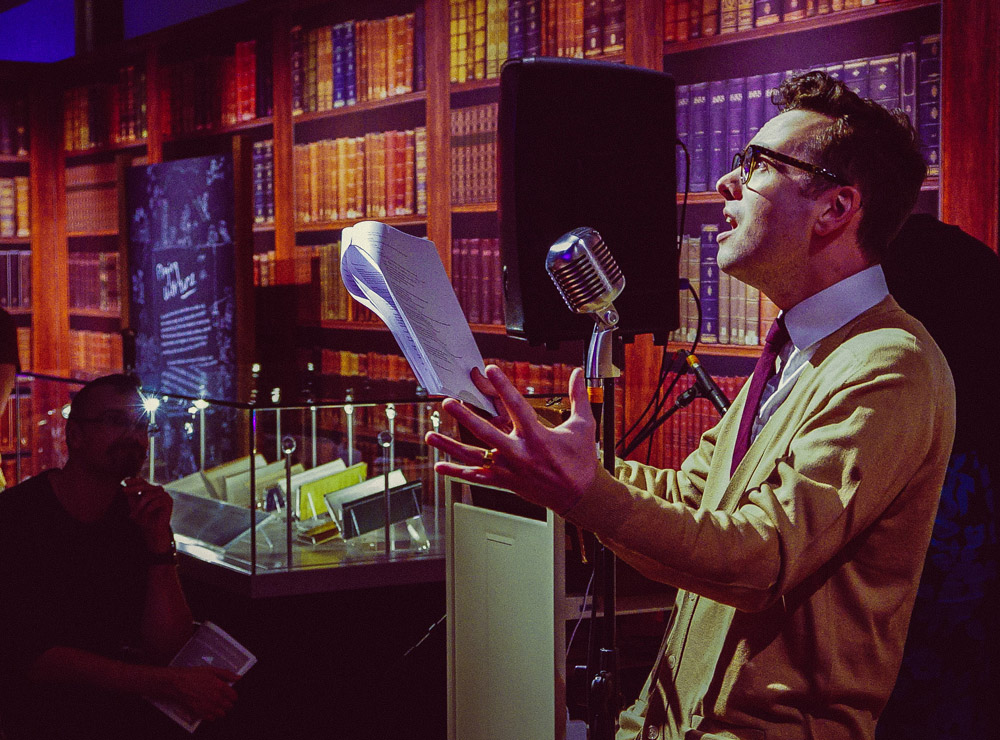

I named it Ark. The concept is to stage immersive short story shows in library spaces, involving cross-arts collaborations and inventive modes of performance, and curated to be site-responsive. Each show involves a unifying theme. I wanted to make the shows performative, memorable, absorbing and surprising for audiences who might, but wouldn’t necessarily, see themselves as literary festival-goers or even as avid readers. I was keen to involve other art forms, like music, dance, sound art, illustration, shadow puppetry and film, and see how they could mesh with live literature in performance and give the texts new lives and new resonances. Novels are often too long to work effectively as a live performance, unless adapted, which reduces and changes the text. With short stories, however, I could present multiple complete literary works in a single performance, curate them in such a way as to vary in mood, genre and style, juxtapose new and classic writing, and feature diverse writers and performers.

Library spaces seemed like the ideal ‘stages’, since there is so much atmosphere seeping from the pages of the books on their walls, and they often have architectural character and untapped potential as performance spaces. Beloved yet beleaguered as libraries are by vicious cuts, I also hoped that the project could, in a small way, help to reanimate and celebrate them.

I was fortunate enough to be funded by the Arts Council to create a series of three initial shows across three libraries in London. Of course, when I came to implement the project, I realised the scale of the practical challenge I had set myself.

Library spaces, it turns out, are really difficult to create performances in. Since their primary purpose is to be open to their readers, usually for long hours, this leaves very little time to set up and rehearse. They tend to be brightly-lit and not well-equipped for performances involving tech. Then there are the difficulties of licensing and commissioning stories, forging collaborations, working out fees, juggling budgets, marketing, delegating, and, in my case, working out how to incorporate my own fiction while still directing shows.

The experience of delivering Ark events made me see live literature in a new light.

But I learned fast and furiously; I had to. And then I experienced the simultaneous stress and reward of watching this unlikely series that I had dreamt up come to life. Afterwards, artists and writers told me how much they enjoyed collaborating, and writers in particular said they found the experience refreshing in comparison to other live literature events. I was cheered to hear how unique as well as enjoyable audiences told me they had found the shows. When one audience member confessed he’d been moved to tears by a story performance, I found myself almost welling up.

The experience of delivering Ark events made me see live literature in a new light. Partly in a more empathetic light, with a better understanding of the practical challenges and costs. But it also intensified my initial view that more is possible in the live literature scene, and that there is a voracious appetite for more among artists and audiences.

Of course, the literary festival, even with the most conventional event format, still has a vital place in literary culture, and can be fantastic in its own way if well-produced. Literary festivals are still growing, so clearly continue to attract audiences. Now that my debut novel, The Invisible Crowd, has been published, I have just started presenting it at festivals and similar events, and have found them a reliably rewarding way to share the work and connect with people in person.

But, for live literature to fulfil its wider potential as an art form, and to truly vivify fiction for new audiences, it needs to be played around with, reconfigured and reinterpreted to foreground both the ‘live’ and ‘literary’ in new, performative and creative ways.

About Ellen

About Ellen

Ellen Wiles is a novelist, literary anthropologist and live literature curator. Her debut novel is The Invisible Crowd (HarperCollins, November 2017). Her first book is Saffron Shadows and Salvaged Scripts: Literary Life in Myanmar Under Censorship and in Transition (Columbia University Press, 2015). She is currently doing a PhD in literary anthropology researching live literature, funded by the AHRC. She is the founder of Ark: an experimental live literature project to create immersive short story performances in library spaces. She was previously a human rights barrister and a musician. She has two children and lives in London.

www.ellenwiles.com

www.arkshortstories.com

About Ellen

About Ellen